Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in Africa: Causes and Symptoms

DLHA Staff Writer

Updated Deecember 7, 2025

Image showing structures affected in Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. Click on image to enlrge.

Although the incidence of PID has decreased in high income countries, it is still relatively high in most African countries. So is the incidence of infertility, due to the fact that the majority of cases are subclinical. Acute PID should be diagnosed and treated early to avoid serious complications.

Although men may have inflammatory diseases affecting different pelvic organs; e.g., prostate, urethra, epididymis, etc., the term Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID) is commonly discussed in the context of women.

In this article, you will learn about Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in Africa from the following viewpoints :

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is defined as the inflammation of the upper genital tract in women that includes the uterus, fallopian tubes, the ovaries and the pelvic peritoneum.

PID can present as an acute (or sudden onset), subacute or chronic condition and can have significant reproductive consequences.

Most often the presentation is subclinical and asymptomatic (i.e. without symptoms) but still with serious consequences.

Due to multiple factors, the incidence of acute PID has decreased in many developed countries, but not so in much of sub-Sahara Africa.

Variable incidence between 0.28% and 1.67% has been reported worldwide.

In sub-Sahara Africa, rates as high as 5.2 - 11% have been reported in hospital populations across different countries.

In Nigeria rates varying considerably from 11 - 70% have been reported in several small hospital samples across the country.

These rates may still be underestimates of community incidence of PID in Africa as many cases of PID are subclinical or self-treated anyway.

Pelvic Inflammatory Diasese results mostly from bacterial infection.

The two most common sexually transmitted micro-organisms (germs) responsible for PID include:

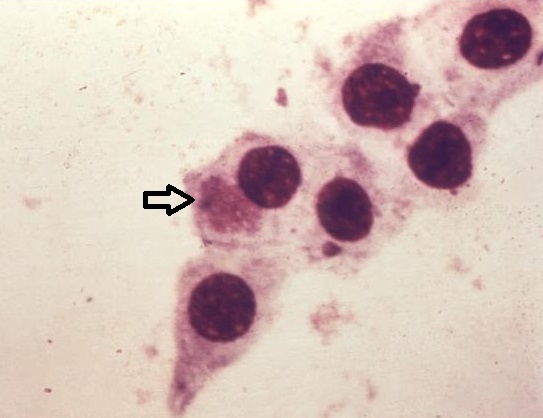

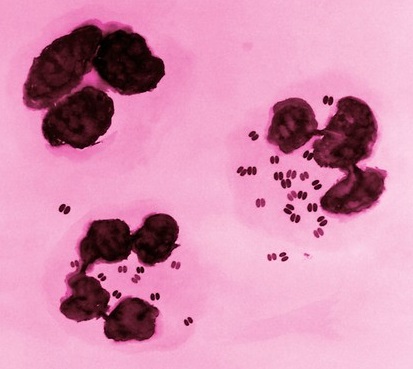

Photomicrograph of Chlamydia trachomatis. Photomicrograph of Neisseria gonorrheae in cells obtained from vaginal swab

Note the presence of a cluster of spore like, C. trachomatis

elementary bodies located intracellularly (at arrow)

inside one of the larger epithelial cells. Credit: US CDC.

About 10% of women infected by Chlamydia trachomatis subsequently develop PID

Non-sexually transmitted micro-organisms (germs) responsible for PID include:

More recent micro-organisms implicated in the causation of PID include:

Photomicrograph of Mycoplama genitalum obtained from vaginal swab in a woman. Click on image to enlarge.

In most cases of PID, many microorganisms are simultaneously involved. The other organisms invade the tissues when the most virulent ones have either begun to destroy tissues or shift vaginal flora to an aerobic state as is the case for bacterial vaginosis.

The risk factors for PID include:

The effects of untreated or poorly treated PID can be significant and sometime life-threatening. They include:

Although the incidence of PID has decreased in high income countries, it is still relatively high in many African countries. So is the incidence of infertility, due to the fact that the majority of cases are subclinical. Acute PID should be diagnosed and treated early to avoid serious complications.

Knowing the social profile of women as well as the common microorganisms (germs) involved in acute PID might help in identifying the group that should be targeted, in order to reduce the bad effects (complications) associated with this disease in a community.

Whereas some women with PID may have acute, serious illness, most patients exhibit few or no symptoms. The most common presenting complaint is lower abdominal pain. In addition, many women report an abnormal vaginal discharge.

You most likely have PID if you have one or more of the following signs and symptoms:

Talk early to your doctor or other healthcare providers if you notice any of the above conditions.

Conditions that may mimic or be confused with PID include:

Resources:

1. Nkwabong E, and Dingom MAN (2015): Acute Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in Cameroon: A Cross Sectional Descriptive Study African Journal of Reproductive Health December 2015; 19(4):90.

2. Oseni TIA.: Occurrence of pelvic inflammatory disease and associated factors among undergraduates attending Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital, Irrua, Edo state, Nigeria. A dissertation submitted to the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria. May 2016. Retrieved Online as a PDF download, March 9, 2023.

3. Jennings LK; Krywko DM. Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. National Library of Medicine. NIH. June 5, 2022.

4. Tough DeSapri, KA. Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. Medscape. Updated August 2021. (Subscription and log in is required to access material).

5. CDC: Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: Treatment Guidelines. 2021. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

Endometriosis: What you need to know Pelvic examination: What is it and why you may need one? What you need to know when you do not have a period?

Published: February 21, 2023

Updated December 7, 2025

© 2023. Datelinehealth Africa Inc. All rights reserved.

Permission is given to copy, use and share content freely without alteration or modification of content and subject to attribution as to source.

DATELINEHEALTH AFRICA INC., is a digital publisher for informational and educational purposes and does not offer personal medical care and advice. If you have a medical problem needing routine or emergency attention, call your doctor or local emergency services immediately, or visit the nearest emergency room or the nearest hospital. You should consult your professional healthcare provider before starting any nutrition, diet, exercise, fitness, medical or wellness program mentioned or referenced in the DatelinehealthAfrica website. Click here for more disclaimer notice.