By: Foluke Akinwalere. Freelance Health Writer. Medical review and editorial support provided by the DLHA Team

Tungiasis (Jiggers infestation) on the heel. Credit

Tungiasis, commonly known as chigoe or jigger infestation, is a parasitic skin infection caused by the penetration of female sand fleas (Tunga penetrans) into the skin of the host.

These tiny fleas, common in tropical and subtropical regions, embed themselves in the skin of the mammals, including humans, to feed on blood and lay eggs.

The condition can cause severe discomfort, pain, and secondary infections if left untreated.

Mainly found in impoverished communities with inadequate sanitation and housing, Tungiasis is listed by the WHO among twenty five Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) and it presents a significant public health challenge, particularly in sub-Saharan African.

In this article, we would explore the details of tungiasis (jigger) infestations in Africans, focusing on its causes, clinical symptoms, diagnosis, treatment options, preventive measures, and the need for collaborative efforts to reduce its impact.

Tungiasis is a skin condition caused by the flea called Tunga penetrans and, in some regions, T.trimamillata. It was added to WHO’s portfolio of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) in 2017. [1]

Tungiasis is a common public health issue in rural and urban slums. It is a zoonoses or zoonotic disease that affects both humans and animals in disadvantaged communities in the Caribbean, sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), and South America, with children and the elderly being the most affected populations. [2].

Tungiasis occurs when the female sand flea burrows into the skin of humans and other mammals to lay eggs. The condition is characterised by the formation of small, inflamed nodules or lesions, typically on the feet, but can also affect other parts of the body.

Tunga penetrans fleas. Click on image to enlarge.

Tungiasis is exclusively caused by female sand fleas called chigoe or jigger fleas (Tunga penetrans). Only female jiggers that are impregnated with eggs can cause tungiasis. Male also bite and feed on the host’s blood, but since they do not have eggs to nurture, they do not burrow into the skin and cause tungiasis.

Tunga penetrans are not strong jumpers and have limited vertical reach, which may explain why most lesions are found on the feet of its host. Belonging to the Siphonaptera order, these tiny parasites possess a remarkable ability to wreak havoc on their hosts.

The occurrence of tungiasis lesions on the toes, between the toes, and on the soles is easily explained by the fact that the most affected individuals are impoverished, walk barefoot, and reside in areas where sand, the habitat of jigger fleas, serves as the ground.

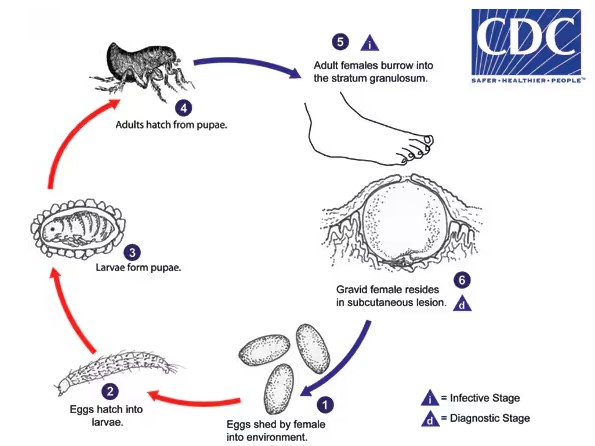

Life cycle of chigoe or jigger flea . Click on image to enlarge. Source: CDC.2016 www.cdc.gov/parasites/

1. The gravid female releases eggs into the environment

2. The eggs hatch into larvae in about 3-4 days and feed on organic debris.

3. Tunga penetrans goes through two larval stages before forming pupae. The pupae are enclosed in cocoons that may be covered with environmental debris like sand or pebbles. The larval and pupa stages last around 3-4 weeks.

4. Adult fleas emerge from the pupae and seek a warm-blooded host for blood meals. Both male and female fleas feed on the host at irregular intervals, but only mated females burrow into the skin of the host, causing nodular swelling.

5. The females use their mouthparts to claw into the skin of the host. Once they penetrate the skin, they burrow into the deeper layers, with only their buttocks exposed.

The females continue to feed and their abdomens can extend up to about 1 cm. The female jiggers lay approximately 100 eggs over a two-week period after which they die and are shed by the host’s skin [3].

The spread of tungiasis is closely connected to human behaviour and environmental conditions that support the growth of sand fleas.

In areas where the disease is common, people are usually exposed to infestation by coming into direct contact with soil or surfaces contaminated with Tunga penetrans eggs.

Walking barefoot or living in crowded, unhygienic environments significantly raises the risk of encountering sand fleas and developing tungiasis. Moreover, certain cultural traditions, like going barefoot during religious or ceremonial occasions, can further increase the chances of infestation.

Understanding how tungiasis is transmitted is crucial for implementing targeted interventions to break the cycle of transmission and lessen the impact of this parasitic infection.

While tungiasis can affect people of all ages and backgrounds, certain factors make some populations more vulnerable. These include: [2]

Identifying and addressing these risk factors can help public health authorities target interventions to protect those most at risk and reduce the impact of tungiasis on affected communities.

Tungiasis infestation has a major impact on communities in Africa. It is prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa. Areas of high prevalence are found in the humid rainforests with sandy soil that are ideal breeding grounds for sand fleas, leading to the extensive spread of tungiasis throughout the continent.

In communities where tungiasis is common, surveys have found rates ranging from 7% to 63%, meaning the spread varies a lot, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO). [4]

A recent study conducted in 2020 reported the pooled prevalence of tungiasis in sub-Saharan Africa to be 33.4%. The study showed the prevalence of tungiasis in specific countries as follows: 46.5% in Ethiopia, 44.9% in Cameroon, 42.0% in Tanzania, 37.2% in Kenya, 28.1% in Nigeria, 22.7% in Rwanda, and 20.1% in Uganda. [2}

Factors associated with an increased risk have already been mentioned above.

The impacts of tungiasis infestation go beyond individual suffering, it affects entire communities and perpetuates cycles of poverty and ill-health.

Children are particularly vulnerable, as infestation can cause them to miss school, struggle academically, and face social stigma.

In adults, Tungiasis can reduce productivity and hinder economic opportunities, worsening existing socio-economic inequalities. Additionally, severe infestations can lead to secondary infections, chronic wounds, and long-term disability, placing additional strain on already strained health systems.

A comprehensive strategy involving key factors in the prevalence of tungiasis in SSA should be developed and put into action by a diverse team of community leaders, healthcare professionals, non-governmental organisations, and policymakers.

Prompt intervention can help mitigate the physical discomfort and psychological distress associated with infestation, promoting overall health and well-being.

Tungiasis is typically diagnosed by visual inspection, the live fleas appearing as whitish discs of varying size with a dark point in the middle that darkens over time until dead and becomes entirely black. In the regions where the disease is common, affected individuals, including children, usually recognise if they have tungiasis. Many affected individuals try to remove the fleas themselves, resulting in a circular lesion with remnants of the dead flea that has turned black. This is a clear indication of recent infection. [4]

Sometimes, tungiasis lesions may resemble those of other skin conditions, including insect bites, furuncles, and some dermatological disorders like scabies or cutaneous larva migrans. Differential diagnosis is essential to distinguish tungiasis from these conditions based on clinical presentation, location of lesions, and patient history.

In some cases, laboratory diagnostic techniques such as microscopic examination of skin scrapings or biopsy samples may be employed to confirm the presence of Tunga penetrans parasites. This can be particularly useful in typical or severe cases where clinical diagnosis alone may not be sufficient.

Accurate diagnosis of tungiasis can be challenging in Africa due to several factors.

Firstly, in areas where tungiasis is common, healthcare providers may have limited familiarity with the condition, leading to misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis.

Additionally, the variable clinical presentation of tungiasis and its resemblance to other skin conditions can further complicate diagnosis. Limited access to diagnostic facilities and resources in rural or resource-constrained settings also contributes to diagnostic challenges.

Treatment of tungiasis involves a multidisciplinary approach, combining pharmacological therapies with mechanical removal of embedded fleas and wound care. The choice of treatment depends on the severity of infestation, the presence of complications, and the patient’s overall health status.

Pharmacological treatments for tungiasis primarily involve topical or systemic medications aimed at killing the embedded fleas and alleviating symptoms. Topical treatments may include the application of insecticides such as benzyl benzoate, permethrin, or ivermectin to the affected areas. Systemic medications like ivermectin or albendazole may be prescribed in severe cases or when multiple lesions are present.

Mechanical extraction of embedded sand fleas is a crucial component of tungiasis treatment. Healthcare providers use sterile instruments to carefully remove the parasites, taking care to minimise trauma and prevent secondary infections. This procedure may be performed under local anesthesia, especially in cases of extensive infestation or when lesions are deeply embedded.

After flea removal, proper wound care is essential to promote healing and prevent complications. This may involve cleaning the lesions with antiseptic solutions, applying topical antibiotics to prevent bacterial infections, and covering the wounds with sterile dressings. Emphasis is placed on maintaining good hygiene and avoiding further exposure to contaminated environments.

While treatment aims to alleviate symptoms and eradicate the parasites, certain complications may arise. These include secondary bacterial infections, allergic reactions to medications, scarring, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation. Close monitoring of patients during and after treatment is essential to identify and manage any complications promptly.

Preventing tungiasis infestation requires a multifaceted approach that addresses individual behaviours, environmental conditions, and community engagement.

Raising awareness about tungiasis and its transmission is essential for empowering communities to take preventive actions. Educational campaigns can disseminate information about the signs and symptoms of tungiasis, mode of transmission, and the importance of early treatment. Targeted messaging tailored to local cultural norms and languages enhances the effectiveness of awareness efforts.

Promoting good hygiene practices is fundamental in preventing tungiasis infesting. Encouraging regular washing of feet and other susceptible areas with soap and water helps remove sand flea larvae and reduces the risk of infestation. Additionally, wearing closed-toe shoes, especially in areas where sand fleas are prevalent, provides a physical barrier against flea penetration.

Addressing environmental factors that contribute to sand fleas proliferation is essential for preventing tungiasis. Measures such as improving sanitation infrastructure, maintaining clean living environments, and removing organic debris where sand fleas thrive can help reduce the risk of infestation. Environmental modifications, such as applying insecticides or deploying larvicidal treatments, may also be considered in endemic areas.

Engaging communities in preventive efforts fosters ownership and sustainability of interventions. Community health workers can conduct outreach activities, distribute educational materials, and facilitate hygiene promotion sessions. Mobilising community members to participate in clean-up campaigns and environmental management initiatives strengthens community-based control measures.

Policymakers play a critical role in prioritising tungiasis prevention on public health agendas and allocating resources for intervention programs. Healthcare providers contribute by integrating tungiasis prevention education into primary healthcare services and ensuring access to preventive measures and treatment. Collaboration between policymakers, healthcare professionals, and community stakeholders is essential for implementing comprehensive prevention strategies.

In conclusion, the prevalence of tungiasis among African populations underscores the urgent need for comprehensive intervention strategies. This parasitic skin infection not only causes physical discomfort and disability but also imposes significant socio-economic burdens on affected communities. Despite being preventable and treatable, tungiasis persists in many regions due to factors such as poverty, inadequate sanitation, and limited access to healthcare. To address this public health challenge effectively, concerted efforts are required at multiple levels, including increased awareness, improved hygiene practices, environmental interventions, and accessible healthcare services. By prioritising tungiasis control and investing in targeted interventions, stakeholders can mitigate the impact of this neglected tropical disease (NTD) and improve the well-being of vulnerable populations across Africa.

Tungiasis is not directly contagious between humans but can occur in clusters within communities due to shared exposure to contaminated environments.

2. Can tungiasis occur in hands?

Yes. Tungiasis occurrence on the hands can be attributed to activities in the sand, as hands are often used to remove sand from other parts of the body.

Yes, certain animals, particularly domestic pets and livestock, can also be affected by tungiasis.

In severe cases, tungiasis may lead to scarring, chronic wounds, and disability, particularly if left untreated.

While rare, severe cases of tungiasis can lead to life-threatening complications such as sepsis or tetanus

Tungiasis infestations typically last several weeks to months if left untreated

Yes, reinfection can occur if preventive measures are not taken or if individuals are re-exposed to contaminated environments

Seek medical attention immediately for diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

1. World Health Organisation (WHO) Report of a WHO Informal Meeting On The Development Of A Conceptual Framework For Tungiasis Control. 11-13 January 2021 [Internet, 2022]. Accessed: May 8, 2024. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/363972/9789240054400-eng.pdf?sequence=1

2. Obebe OO, Aluko OO. Epidemiology of tungiasis in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pathog Glob Health. 2020 Oct;114(7):360-369. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2020.1813489. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7586718/

3. Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC). Tungiasis. [Internet. Last reviewed: 2017 Dec. 31]. Accessed, May 7, 2024). Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/tungiasis/index.html.

4. World Health Organisation. Tungiasis [Internet. April 28, 2023]. Accessed May 8, 2024]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tungiasis

Recommended reading:

5 Common Skin Diseases in Africa

Published: May 12, 2024

© 2024. Datelinehealth Africa Inc. All rights reserved.

Permission is given to copy, use and share content freely for non-commercial purposes without alteration or modification and subject to attribution as to source.

DATELINEHEALTH AFRICA INC., is a digital publisher for informational and educational purposes and does not offer personal medical care and advice. If you have a medical problem needing routine or emergency attention, call your doctor or local emergency services immediately, or visit the nearest emergency room or the nearest hospital. You should consult your professional healthcare provider before starting any nutrition, diet, exercise, fitness, medical or wellness program mentioned or referenced in the DatelinehealthAfrica website. Click here for more disclaimer notice.